Does Silica Cause Kidney Disease?

The Steenland et al. 2002 paper on "Pooled Analyses of Renal Disease Mortality and Crystalline Silica Exposure in Three Cohorts"1 is very convincing of an association between silicosis and renal disease, but it does not rule out confounding variables. The role of confounding must be considered because of our lack of knowledge about the pathophysiology of renal and autoimmune diseases associated with silica exposure. "The pathogenesis of autoimmune and renal disease in silica-exposed workers is not clear."2 As Steenland says in a later paper published in 2005, "Overall the evidence is still too sparse to be summarized as conclusive, but it seems very probable that silica causes kidney disease."3 Steenland does not raise the question about possible confounding variables in either paper.

What is confounding?

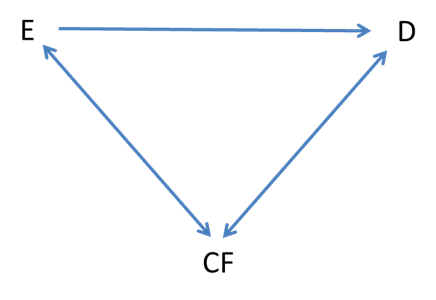

Figure 12-1 Interrelationship between an exposure (E), confounding factor (CF), and disease (D).4

"The third alternative explanation that must be considered is that an observed association (or lack of one) is in fact due to a mixing of effects between the exposure, the disease, and a third factor that is associated with the exposure and independently affects the risk of developing the disease. This is referred to as confounding, and the extraneous factor is called a confounding variable.

Confounding can lead to either the observation of apparent differences between study groups when they do not really exist or, conversely, the observation of no differences when they do exist. For example, a number of observational epidemiologic studies have shown an inverse relationship of consumption of vegetables rich in beta-carotene with risk of cancer. While it may be the beta-carotene itself that is responsible for this lower risk, it is also possible that the association is confounded by other differences between consumers and nonconsumers of vegetables. It may not be the beta-carotene at all, but rather another component of vegetable such as fiber, which is known to reduce cancer risk,. In addition, those who eat vegetables might also be younger or less likely to eat fat or to smoke cigarettes, all of which in themselves might reduce cancer risk. Thus, the observed decreased risk of cancer among those consuming large amounts of vegetables rich in beta-carotene may be due, either totally or in part, to the effect of these confounding factors."5

In this example, E = beta-carotene; D = cancer; and CF = fiber.

"Intuitively, confounding can be thought of as a mixing of the effect of the exposure under study on the disease with that of a third factor. This third factor must be associated with the exposure and, independent of that exposure, be a risk factor for the disease. In such circumstances the observed relationship between the exposure and disease can be attributable, totally or in part, to the effect of the confounder. Confounding can lead to an overestimate or underestimate of the true association between exposure and disease and can even change the direction of the observed effect. For example, consider a study that showed a relationship between increased level of physical activity and decreased risk of myocardial infarction (MI). One additional variable that might affect the observed magnitude of this association is age. People who exercise heavily tend to be younger, as a group, than those who do not exercise. Moreover, independent of exercise, younger individuals have a lower risk of MI than older people. Thus, those who exercise could have a lower risk of MI quite apart from any effect of this habit simple as a consequence of the greater proportion of younger individuals in this group. In this circumstance, age would confound the observed association between exercise and MI and result in an overestimate of any inverse relationship."6

In this example, E = exercise; D = MI; and CF = age.

Are autoimmune diseases caused by infections?

Currently, there is a lack of understanding about the nature of autoimmune diseases, some of which are associated with silicosis. Since they are not fully understood, then there could be confounding factors of which we are unaware. How about the role of infections in causing autoimmune diseases? For rheumatoid arthritis, "Purported triggers in addition to smoking have included bacteria (Mycobacteria, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori), viruses (rubella, Epstein-Barr virus, parvovirus), superantigens, and other undefined factors."7 Also see "Cell Damage and Autoimmunity: A Critical Appraisal"8 and "The role of infections in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases."9

In this example E = silica exposure; D = autoimmune diseases (including kidney disease); and CF = infection;

Is the kidney disease associated with silicosis autoimmune in type?

In the NIOSH Hazard Review, the authors discuss together autoimmune and kidney diseases: "In addition to these case reports, 13 post-1985 epidemiologic studies reported statistically significant numbers of excess cases or deaths from known autoimmune disease or immunologic disorders (scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcoidosis), chronic renal disease, and subclinical renal disease. . . . The pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis and other renal effects in silica-exposed workers is not clear. . . . The cellular mechanism that leads from silica exposure to autoimmune diseases is not known."10

Regarding the mechanism of the kidney damage, Steenland et al. write in the 2002 paper, "an autoimmune mechanism has been postulated, although direct toxicity to the kidney is also possible. However, the silica-renal disease association is still not widely accepted and the literature to date remains somewhat sparse."11

Could treatment of silicosis with certain drugs be a confounding variable?

Another potential confounding variable is the use of drugs for the treatment of silicosis. According to Gerald S. Davis, the author of the "Silica" chapter in the Harber textbook, "Corticosteroid treatment may be directed at reducing the inflammatory response to silica through its actions on lymphocytes, macrophages, and other cells. . . . A trial of daily prednisolone for 6 months was carried out among 34 stone-crushing workers with silicosis in India."12 Side effects or corticosteroids include diabetes and increased risk of infection,13 both of which could increase the prevalence of diabetic and autoimmune kidney disease in the cohort compared to the control population if one assumes that immune suppression could increase the risk of infection-based autoimmune diseases.

Does silica-associated tuberculosis help us with this question?

If infection is a confounding variable that interacts with silica exposure and immune-based kidney disease, then silica does not cause kidney disease in the same way that silica does not cause tuberculosis. Infections are cause by microbial organisms, not minerals. But as the Steenland et al. 2002 paper shows, silicosis is associated with kidney disease and tuberculosis. There is some evidence that silica exposure alone without silicosis is associated with tuberculosis, "Some evidence indicates that workers who do not have silicosis but who have had long exposures to silica dust may be at increased risk of developing TB. Two epidemiologic studies reported that, compared with the general population, a threefold incidence of TB cases occurred among 5,424 nonsilicotic, silica-exposed Danish foundry workers employed 25 or more years."14 Because tuberculosis spreads after close human-to-human contact, this evidence could be questioned--workers in foundries with active TB could spread it to co-workers, including those with and without silicosis.

In a paper entitled "Silicosis Mortality with Respiratory Tuberculosis in the United States, 1968-2006," the authors state, "This study has shown a significant decline in silicosis-respiratory TB mortality in the United States during 1968-2006." and "While comorbidity and comortality with silicosis and TB once represented such a prevalent scourge that 'silicotuberculosis' had a discrete ICD code, 2006 marks the first year in which no silicosis-respiratory TB deaths were recorded among residents of the United States."15

If silica-exposed workers had increased risk for kidney disease in the 1930s, do they now?

As seen in the previous section, U.S. workers are no longer getting silicotuberculosis. Is it not likely, that they are also no longer getting silicosis-associated kidney disease? The cohorts examined by Steenland et al. in the 2002 paper were in three groups: 4626 industrial sand workers employed in 18 plants from the 1940s to the 1980s; 3348 gold miners employed for at least 1 year between 1940 and 1965; 5408 granite workers employed during 1950-82 and x-rayed at least once in a silicosis surveillance program. "Follow-up for this cohort began at time of first employment or 1950, whichever was later, and continued until death or 31 December 1994."16 Many in this cohort would have worked in the 1930s and 1940s, in the early days before modern dust control measures were enforced.

A later cohort studied by Calvert et al. was based on 4 million death certificates from 27 states for the period from 1982 to 1995. This study found no significant association between crystalline silica exposure and several different renal diseases.17

NIOSH studied kidney disease in gold miners. "The highest risk was in workers hired before 1930. In these workers, we found 10 cases but expected 4 or 5. The risk was not increased in workers hired after 1930."18

The author of the "Silica" chapter in the Harber textbook writes, "Workers employed before 1940 were exposed to high dust levels, exceeding 40 mppcf. Workers employed after the institution of dust controls in 1940 were exposed to levels below the current permissible exposure limit (PEL), less than 10 mppcf. Deaths due to silicosis and TB were common among workers hired before 1940, with SMRs that were 5 to 10 times those expected for the general U.S. population. Virtually no deaths due to silicosis were observed among workers who had exposure in the granite industry after dust control measures were instituted. Pulmonary function was preserved in current granite workers, with no loss over time beyond the expected effects of aging and smoking. Chest radiographs from 972 workers revealed only 7 films with small rounded opacities that were suggestive of silicosis, and all of these were of mild degree."19

Steenland K, Mike Attfield M, Mannejte A. Pooled Analyses of Renal Disease Mortality and Crystalline Silica Exposure in Three Cohorts. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002; 46 (suppl 1):4-9. Full text available at http://annhyg.oxfordjournals.org/content/46/suppl_1/4.abstract

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Hazard Review: Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica, p. vi. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-129/pdfs/2002-129.pdf. Accessed 11 September 2016.

Steenland K. One agent, many diseases: exposure-response data and comparative risks of different outcomes following silica exposure. Am J Ind Med. 2005; 48(1):16-23. [PMID 15940719]

Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1987, p. 289.

Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1987, p. 36.

Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1987, p. 287-8.

Goldman L, Schafer AI (eds). Cecil Medicine, 24th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2012.

Mackay IR, Leskovsek NV, Rose NR. Cell damage and autoimmunity: a critical appraisal. J Autoimmun. 2008; 30(1-2):5-11. [PMID 18194728]

Samarkos M, Vaiopoulos G. The role of infections in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005; 4(1):99-103. [PMID 15720242]

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Hazard Review: Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica, p. 68. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-129/pdfs/2002-129.pdf. Accessed 11 September 2016.

Steenland K, Mike Attfield M, Mannejte A. Pooled Analyses of Renal Disease Mortality and Crystalline Silica Exposure in Three Cohorts. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002; 46 (suppl 1):4-9.

Harber P, Schenker MB, Balmes JR (eds). Occupational and Environmental Respiratory Diseases. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996, p. 394.

Mayo Clinic. Prednisone and other corticosteroids: Side effects of oral corticosteroids. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/steroids/art-20045692?pg=2. Accessed 11 September 2016.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH Hazard Review: Health Effects of Occupational Exposure to Respirable Crystalline Silica. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2002-129/pdfs/2002-129.pdf. Accessed 11 September 2016, p. 34.

Nasrullah M, Mazurek JM, Wood JM, Bang KM, Kreiss K. Silicosis mortality with respiratory tuberculosis in the United States, 1968-2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2011; 174(7):839-48. [PMID 21828370]

Steenland K, Mike Attfield M, Mannejte A. Pooled Analyses of Renal Disease Mortality and Crystalline Silica Exposure in Three Cohorts. Ann Occup Hyg. 2002; 46 (suppl 1):4-9.

Calvert GM, Rice FL, Boiano JM, Sheehy JW, Sanderson WT. Occupational silica exposure and risk of various diseases: an analysis using death certificates from 27 states of the United States. Occup Environ Med. 2003; 60(2):122-9. [PMID 12554840]

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Gold Miners (Silica Exposure) (1). Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pgms/worknotify/goldminer.html. Accessed 11 September 2016.

Harber P, Schenker MB, Balmes JR (eds). Occupational and Environmental Respiratory Diseases. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996, p. 386.

Revised: May 30, 2018